EXPLAINING THE GRID PART 2

Economics

Imagine a grocery store that does not list prices for anything sold in the store. When you go through the checkout line only the number of items that you have purchased are noted—with no identification at checkout of what the items are—and you leave without paying anything. At the end of each month, you get a bill charging you for the total number of items that you purchased during the month. This bill again does not list the prices of the individual items or even what you purchased.

Instead, the store determines the total cost of all goods that it sold to all customers that month to derive an average cost per item. Your bill is then determined by multiplying the number of items you purchased times this average cost. If the average cost of goods sold by the store is $10, and you bought 20 items, then your bill is $200. You pay this price whether you bought the most expensive steaks, wines, and prepared foods, or bottled water, bread, and bananas.

As crazy as it sounds, this is essentially the way that electricity has been sold to most retail customers for decades. You are probably thinking that I have not chosen a very good analogy here. After all, a grocery store sells hundreds, or thousands, of different goods, while electric bills apply to the sale of only one thing: electricity.

But, as we saw in my previous post on the cycles of electric use (Explaining the Grid, Part 1), the cost to generate electricity at any moment in time is highly variable, depending on the total load at that time and the cost of the generation units that are operating to serve that load. Indeed, the cost of electricity in some markets is recalculated every five minutes. The purchase of electricity in each time period in which the cost to generate electricity in an electric system has changed can be thought of as equivalent to the purchase of a separate item for sale in our imaginary grocery store. The cost to generate electricity in some hours is relatively low, like the cost of water or bananas, and the cost in other hours can be quite expensive, like the cost of a good wine or a prime cut of beef.

Yet, when you get up in the morning and turn on the lights, do you know, or even think about, the cost of the electricity used to make the lights go on? Not likely, and even if you knew the cost to generate the electricity you are using at any point, that information is only distantly relevant to your monthly electric bill. Just as there are no prices for individual items purchased in our imaginary grocery store, most people’s electric usage is recorded on a meter that records only the amount of electricity being purchased, not the cost of that electricity. And that meter is read only once a month. Because the cost of the electricity you purchase isn’t recorded by your meter, your bill doesn’t reflect whether you are using electricity in the most expensive peak hours of the month, equivalent to the most expensive items in the grocery store, or at midnight when electricity tends to be much cheaper.

Let’s add one more assumption about our grocery store. Suppose that the store is obligated by law to always have everything in stock, and the store can never be in a position where it is unable to supply something a customer wants. That means the store must pay whatever its suppliers charge for the goods the store needs to buy, no matter how expensive. There may be competition among suppliers selling goods to the store, but if the store needs to buy almost all of a good that suppliers have to sell, then the store will have to pay the price of the most expensive supplier.

No grocery store would agree to operate under such an obligation. But Grid operators have been obligated for decades under a number of longstanding state and federal statutes to supply all load. As a result, by now we have gotten used to our lights going on when we want them to regardless of the cost (which we almost never think about). This obligation to supply all load on demand has major implications for Grid operations, as we shall see in some of my subsequent posts.

There are important reasons why electricity is sold this way. Most people today do not have access to storage facilities such as batteries. The electricity they use must be supplied at the time they use it, regardless of the cost. It’s not like a grocery store where you can purchase goods in bulk when they are on sale for use at a later time when prices for that good are high or the good is not available.

And most people use at least some amount of electricity continuously, twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, fifty-two weeks a year. It is extremely complicated to keep track of the price of electricity at the time it is sold to each individual customer over each 24-hour period to then be used for billing purposes. And it is even more complicated to provide this information to customers on a real-time basis that would allow them to consider costs and perhaps change the amount of electricity they are using. The technology that could be adapted to provide this information has not been available until recently, and to date the use of any technology for this purpose has not been widely implemented.

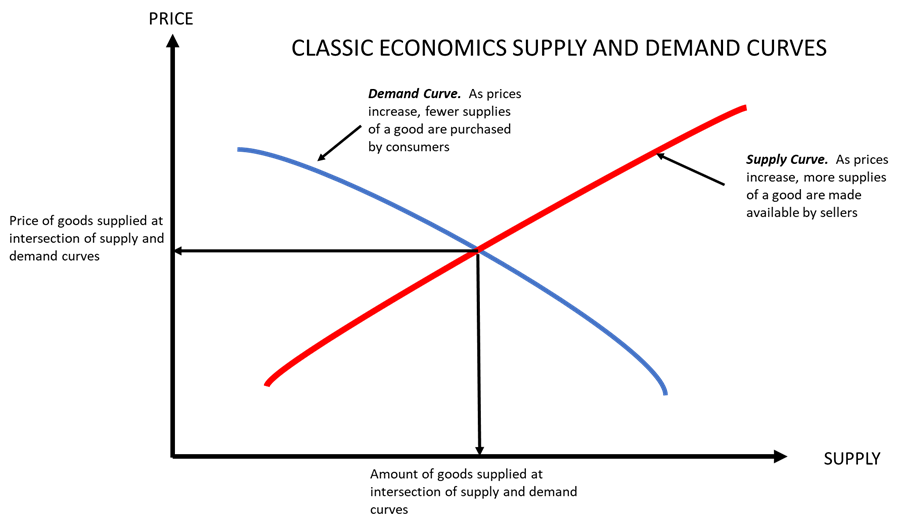

As a result, the economics of the electric industry are unique, and turn standard economic theory on its head. Those of you who have taken an introductory economics course will recognize the following type of supply and demand curve graph depicting the classic economic theory explanation of how prices are set in a competitive market.

If you haven’t taken an introductory economics class, or if you have but don’t remember much about it, this graph illustrates the commonsense proposition that sellers will offer to sell more of a good when prices increase, and consumers will purchase fewer of those goods when prices increase. The price for the goods and the amount of the goods supplied is established at the intersection of the two curves. If sellers raise the price above this point, consumers will not purchase all of the goods made available by sellers because the price is too expensive. If consumers will only pay a lower price than the price at this point, suppliers will not make available all of the goods consumers would purchase at that price because the price is too low.

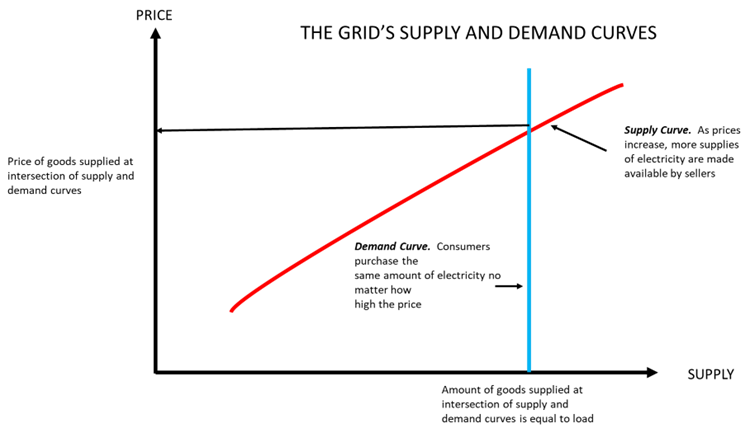

The demand curve that applies to the Grid looks quite different. It’s not a curve at all, but a straight vertical line.

You don’t consider the cost of electricity when you turn on your lights when you wake up in the morning or when you run your dishwasher in the afternoon and, in any event, your electric bill is not based on the cost of electricity at those times. As a result, when you do either of those things, you are indifferent to the cost of electricity at the time you do them. Instead, you consider only whether you need light or to run your dishwasher, and if so you turn them on without any thought of price. The demand curve on the Grid is, in essence, a vertical line pointing straight up, indicating that consumers will purchase the same amount of electricity regardless of its cost.

The effect of this unique vertical demand curve has important consequences for the Grid. Grocery stores can estimate how much the price of an item will affect demand and, from this, determine how much of that item to stock. And if they are wrong and do not stock enough, the only consequence is a disappointed customer who can go to a different store.

Grid operators, however, can’t rely on price to moderate demand because almost no one knows the price that will be charged for electricity when they turn on an electric device. And Grid operators can’t decide to turn away customers rather than obtaining more electricity because they have a legal obligation to serve and the consequences of running out of electricity are severe. Major outages result in lengthy investigations, significant fines, private lawsuits, and reputational damage. This means that Grid operators must accurately predict electric loads based on factors such as the time of year and the weather, and then ensure they have enough supply to meet this load, plus a healthy reserve in case they are wrong, no matter the cost.

Economists will say that this is not an efficient way to run the Grid, or any industry. To be sure, you are unlikely to shut off your air conditioning when it is over 90 degrees outside (like it is for me as I write this). But high costs for electricity could, if you knew what they were and had to pay those costs, cause you to run your dishwasher and washing machine in the evening or early morning when costs are lower. If enough consumers were to move some of their use of electricity away from the higher cost periods, it could have a significant effect on the amount of generation capacity used on the Grid with potentially major cost savings to customers.

There are two arguments that consumers are not as indifferent to the cost of electricity as I am suggesting. The first argument is that consumers are willing to purchase more efficient appliances and other electric devices when electricity prices in general are higher. Use of these more efficient devices then saves those customers money by reducing their total use of electricity.

But the purchase of more efficient appliances does not affect when a customer uses those appliances. Instead, use of more efficient electric devices is equivalent, in our hypothetical grocery store, to a customer purchasing fewer of the items that have no identified price. The fact that consumers own more efficient devices does not mean that they will change the time that they use their dishwashers, dryers, and other appliances based on the cost of electricity, but only that they will use a lower total amount of electricity each month. And it is this short-term indifference to changes in costs during the day that is most important to the daily operations of the Grid.

The second argument that consumers are not indifferent to the cost of electricity points to the relatively minor, but increasing use of what is called “demand-side management” to reduce demand when supply is short and prices are high. There are a variety of demand-side management programs, but they all essentially involve Grid operators making payments to consumers to reduce their use of electricity instructed to do so.

I agree that demand-side-management programs can be useful in managing electric demand. But these programs do not in any way indicate that electric consumers are sensitive to the costs of electricity. If consumers in fact reacted to changes in the cost of electricity, they would automatically reduce their consumption when costs are high. The fact that consumers must be paid by Grid operators to reduce their use of electricity means that the costs incurred to generate electricity do not by themselves have any influence on the consumption of electricity.

In my next post I will try to provide a further explanation of energy markets, a subject I briefly addressed in one of my posts on RTOs.

I hope you enjoyed this post. I enjoy writing them, and will never charge for subscriptions or ask for donations. I only ask that, if you did enjoy it, you press the “like” button below. Doing so will help me evaluate interest in the book I am writing on grid operations. Of course, if you have a reaction to, or question about, this post, please leave a comment and I will be happy to respond.

You write with clarity and break it down to an understandable level.