WHO DOESN'T PAY FOR TRANSMISSION UPGRADES?

The Potential for Customers to Benefit from Upgrades While Avoiding the Responsibility to Help Pay for Them

After a brief diversion in my post last week to talk about environmental reviews of energy projects, I am back this week to continue the next installment posts about transmission issues. My last transmission-related post addressed who pays for transmission upgrades. This post addresses the opposite question. Who doesn’t pay for transmission upgrades? Who is able to freeload off upgrades paid by others?

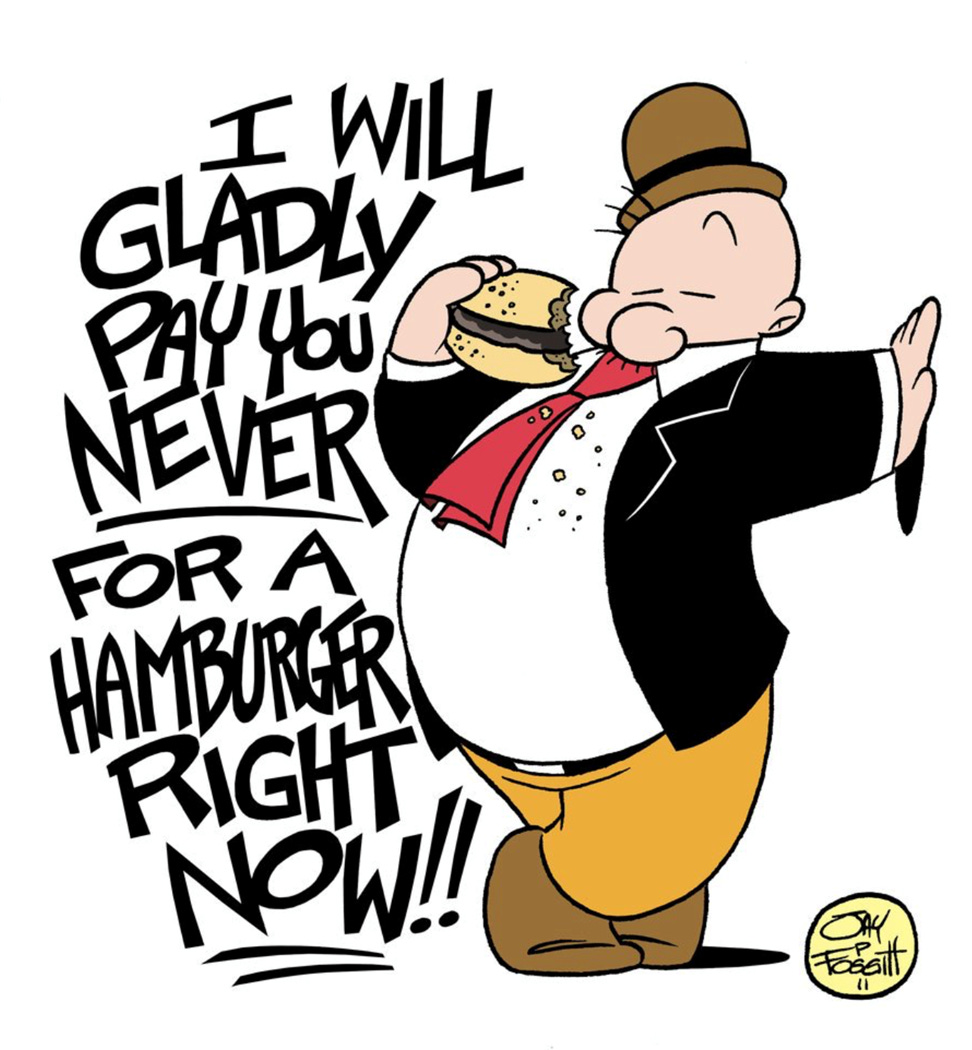

First, let me use yet another analogy to help explain how it could happen that someone could benefit from an upgrade to transmission facilities or from the construction of a new line without having to contribute to its cost. Suppose a new housing development is being constructed at the end of a long gravel road that already serves a number of houses along the way. The owner of the development knows that not many people will want to buy an expensive new house that can only be reached on a long gravel road, and almost no one will want to do so if they have to pay the exorbitant prices the developer hopes to get. So, the developer decides to pay to have the road paved. The cost of paving the road will be more than made up by the high prices the developer will be able to charge once the road is paved. But paving the road doesn’t benefit only the developer and the purchasers of the houses in the development. It also benefits all the existing homeowners who already use the road being paved. And they didn’t have to pay one cent.

For similar—but not identical—reasons, some customers can benefit from upgrades to transmission lines, and even new transmission lines without having to contribute to their cost. Transmission upgrades or additions can strengthen the transmission system regionwide. This can improve system reliability for a wide range of regional customers or eliminate a constraint that affects electricity prices far away from the location of the upgrade. These benefits can accrue to customers even if, unlike my analogy, those customers do not transmit any electricity over the new transmission facilities.

However, the circumstances under which customers can freeload off transmission upgrades constructed by others are more complicated, and more limited, than in my paved road analogy. The last job I had at FERC was to defend its orders. In that job I was involved with two cases addressing circumstances when customers potentially could have avoided paying costs for system upgrades. I will use these cases to help illustrate the ways that this can happen.

Freeloading is typically not an issue in a Regional Transmission Organization (RTO). Most transmission upgrades and new transmission lines providing regional benefits in an RTO must be planned and approved in a central RTO planning process. Part of that process includes developing a method for allocating the costs of the upgrades. There can be disputes over those cost allocation methodologies, as I explained in my previous post Who Pays for Transmission Lines?, explaining how transmission upgrades costs are allocated. But it generally does not happen that a customer who receives measurable benefits from an upgrade is not allocated any costs at all.

There is one potential exception that can apply in at least some RTOs. Most RTOs have individual transmission zones that consist of the service territories of the utilities that transferred operational control over their transmission facilities to the RTO. These zones have several different purposes, one of which is the allocation of costs. Many zones include, in addition to the utility for which the zone is named, one or more small municipal utilities or co-ops that traditionally were wholesale customers of the utility and that owned limited transmission facilities used to serve its customers. The costs of all transmission facilities in the zone are allocated between the utility and the small utilities based on the size of their customer demands. For example, if the large utility serves 95% of the customer demand in the zone and a small co-op serves 5%, the large utility will be allocated 95% of all transmission line costs in the zone and the co-op will be allocated 5% of the costs. The costs of regional upgrades allocated to a transmission zone are shared in the same way.

Some RTOs allow utilities in a transmission zone to skip the RTO’s regional planning process for upgrades located in that single zone and have no effect in other zones. Traditionally, costs of these one-zone upgrades were automatically included in the costs shared between the large utility and the small utilities located in the zone. However, recently claims were raised that some utilities were gold-plating new transmission facilities and pushing the costs onto the other utilities in the zone. For example, a small co-op could install an expensive $100 million transmission line that provides relatively few benefits to the zone and have the large utility pay $95 million of those costs.

To address this concern, at least one RTO changed its cost allocation rules to allow the utilities in a zone to vote whether they want to share in the costs of proposed upgrades that were exempt from the regional planning process. If the vote of all transmission owners in the zone was not high enough to approve cost sharing, the utility proposing the upgrade could either withdraw the proposed upgrade or bear all the costs itself. Some large utilities objected to the modification because it would allow the smaller utilities to avoid paying the costs of needed upgrades by voting against cost sharing.

FERC approved this proposal over the objections of some of the large utilities. FERC reasoned that all customers would have an incentive to vote in favor of proposed upgrades truly benefiting all customers in the zone because if the proposal was rejected the upgrade might never be built and the benefits of the project would not be obtained. I represented FERC in the appeal, and won against one of my friends who represented the objecting utilities. But despite my victory, it remains the case that this provision allowing customers to object to the allocation of the costs of a proposed upgrade can allow them to receive the benefits of the upgrade without paying for them if the customers vote against cost sharing for an upgrade and it is constructed anyway.

To be fair, what I have just described is a very minor, and mostly theoretical, way that customers can avoid paying for the costs of beneficial transmission upgrades. Most RTOs don’t have a provision allowing for votes over cost sharing. Further, to my knowledge, no utility has avoided cost sharing for a beneficial project that was constructed anyway. I mention this potential way to avoid cost sharing primarily because it helps to illustrate how the transmission allocation process works (and, of course, because it lets me describe a case I won).

Freeloading is more of an issue outside of the RTOs, however. There, an outcome similar to my analogy is more plausible. A transmission owner may have an incentive to construct an upgrade or new transmission line that benefits other transmission owners, just as the developer in my analogy had an incentive to pave the gravel road in order to make its new housing development more profitable. This incentive made it worthwhile for the developer to do so, even though paving the road also benefited the existing homeowners who previously had used the gravel road. And in both my analogy and in the real world, absent an agreement to pay, those who benefit from the upgrade have no obligation to a share of the costs of the upgrade.

FERC has recognized this problem. To address it, FERC issued a series of orders obligating transmission owners in a region to engage in joint transmission planning even if they are not in an RTO. These orders attempt to replicate the transmission planning process in RTOs, where all the transmission owners in a region agree on a plan to construct transmission facilities that provide a regional benefit, and also agree to the allocation of the cost of those facilities. The most recent series of orders has faced pushback from those who assert it intrudes upon the states’ authority over the siting and construction of transmission facilities. But the earlier FERC orders imposing a general regional planning obligation have been upheld on appeal.

The primary reason for the regional planning orders was to ensure the construction of the most efficient transmission facilities for the region. These regional facilities typically are relatively expensive on an absolute basis, but less expensive than the total costs of the construction of a patchwork of smaller facilities by the individual utilities in the region. But a subsidiary reason for FERC’s regional planning orders was to address freeloading concerns and to ensure that all transmission owners who benefit from a transmission upgrade are responsible for paying their fair share of the costs. FERC’s orders have improved regional transmission planning outside of the RTOs and reduced the potential for customers to benefit from transmission upgrades they don’t pay for.

There is, however, a hole in FERC’s regional transmission planning orders. FERC has jurisdiction over investor-owned utilities and can order them to participate in regional planning. But FERC has no jurisdiction over the smaller municipal utilities or co-ops or similar utilities (non-jurisdictional utilities). These non-jurisdictional utilities can voluntarily agree to participate in the regional planning organizations that FERC mandated. And if they do, they are subject to the same cost-sharing requirements as investor-owned utilities. But if the non-jurisdictional utilities do not agree, FERC cannot force them to join. Nor, if they have not joined, can FERC order these non-jurisdictional utilities to pay for any benefits received from other utilities’ construction of new regional facilities.

What FERC can do is tell the utilities participating in a regional planning process that they do not need to consider the needs of the non-jurisdictional utilities when conducting their regional planning if the non-jurisdictional utilities do not participate in the process. This frequently provides adequate incentives for non-jurisdictional utilities to participate even if FERC cannot require them to do so. Because costs typically are allocated based on each utility’s share of customer demand, it frequently is the case that the small non-jurisdictional utilities’ share of the costs of a regional facility that addresses their needs is much less than if those utilities had to pay all of the costs of a smaller facility were required to construct just to serve themselves.

But this is not always the case. Because transmission upgrades can have regional effects, non-jurisdictional utilities can obtain benefits of those upgrades without participating in the regional planning process or agreeing to pay a share of the costs. This can happen even if the non-jurisdictional utilities’ needs are not considered in the planning process. Depending on the circumstances, these small utilities might decide that it is more economic not to participate.

This was the issue in the second case I was involved with when I was at FERC. There is a region in the western plains and desert states that is very large geographically, but with sparse populations widely spread out. About half of the utilities in this region are large investor-owned utilities that are subject to FERC’s jurisdiction, and half are non-jurisdictional utilities that FERC cannot require to participate in a regional transmission planning group. Because the population centers are spread out, it is virtually impossible for the investor-owned utilities to construct any regional transmission facilities that will not also confer significant benefits on the non-jurisdictional utilities.

The investor-owned utilities were concerned that these atypical conditions would create strong incentives for the non-jurisdictional utilities to freeload from the regional transmission upgrades that might be identified as a result of the planning process. They asked FERC to allow them to revise their regional planning process. The proposed revisions would have applied to the evaluation of a proposed upgrade providing significant benefits not only to the utilities participating in the regional planning group, but also to non-jurisdictional utilities that had not joined the group. The investor-owned utilities proposed that, in this circumstance, the investor-owned utilities would not be obligated to construct the upgrade unless the benefitting non-jurisdictional utilities agreed to pay a share of the costs.

FERC rejected this proposal, and the investor-owned utilities appealed. The Court of Appeals held that FERC had not adequately supported its decision and sent the case back to FERC to either provide a better explanation or come up with a new proposal. As a result, it still is not known whether or how freeloading will be possible in this region.

Since I bragged about winning the first case I discussed, I am sure you are wondering if I will take the blame for FERC’s loss in this second case. Well, the answer is no I will not. The brief in the case was written by another attorney who left before the oral argument was conducted. I was asked to do the argument and had almost fully prepared when an argument was scheduled for the next day in a case I had briefed. One of the two arguments was in New Orleans and the other in Washington DC. I couldn’t do them both, so someone else had to take over the argument in the case that is the subject of this post. Since I didn’t write the brief or do the argument, I think I am fully justified in not taking the blame for the loss. But I do take the responsibility for the other case where I both wrote the brief and did the argument. I won, of course.

[Note: I am going to be very busy the next couple of weeks so it will be two or three weeks before I do another post]

***

I hope you enjoyed this post. I enjoy writing them and will never charge for subscriptions or ask for donations. I only ask that, if you did enjoy it, you press the “like” button below. Doing so will help me evaluate interest in the book I am writing on grid operations. Of course, if you have a reaction to, or question about, this post, please leave a comment and I will be happy to respond.

I spent my career at a municipal, we were/are part of BANC BA. It may seem a bit unfair, but we used mostly WAPA Transmission that was public only. Our Path 66 rights were on The Oregon _ California Transmission project that PG&E tried to block for years. It was built by public power for public power and is operated by public power. The vast majority of the 500kV transmission in the Pacific Northwest was built by and is operated by Bonneville Power Administration. TVA built and operates broad swaths of Transmission in the South. I might take your comments that public power takes a free ride with a grain of salt.

Matt, are these “community choice” power entities we have in California examples of non-jurisdictional utilities? I’m trying to figure out how they add value, if indeed they do at all.